During a night in which I could not sleep, I decided instead to finish a reading assignment for an upcoming event and read through Dr. Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

During a night in which I could not sleep, I decided instead to finish a reading assignment for an upcoming event and read through Dr. Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

I had read it before, of course, studied it—as all Americans should—in school. But in the light of the current day, and in this particular moment in my own life, the text touched me as never before.

There are, of course, several aspects to the letter: the frustration that King felt when “moderate whites” whose support he expects, instead tell him that his timing is off, that the moment to act has not yet come (“For years now I have heard the word ‘Wait!’…This ‘Wait’ has almost always meant ‘Never.’”); the pressure that he felt as he stood between the forces of “the ‘do-nothingism’ of the complacent” and the “hatred and despair of the black nationalist;” and the need to stand against what he saw as a series of “unjust laws” and the fundamental need that he felt that all people have to be equal, not only in the eyes of the law but in the heart of the nation.

This section is in so many ways the heart of the letter. Before he begins to churn within with the preachers’ fire, before the wind-up into the lofty realms of rhetoric, King’s simple words cut like a knife:

“An unjust law is a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself. This is difference made legal. By the same token, a just law is a code that a majority compels a minority to follow and that it is willing to follow itself. This is sameness made legal.”

What does it mean that, were I to leave the state in which I live and drive a few miles to the west, to Pennsylvania and beyond, that I, a married man, would devolve into being unmarried? What does it mean that, in so many states, I could be denied the right to work, the right to have a place to live, just for being the person I am? What does it mean if I, and others like me, have to live a life of looking over our shoulders, of more or less constant concern for personal safety, and if, as we have recently seen time and again, I or any group of us, fall prey to violence, the police are slow to action and quick to blame the victim?

What does it mean if in the moment I wish to celebrate my own wedding, I can be denied the right to buy a fucking cake because my need for celebration apparently flies in the face of “Good Christians” everywhere? Or that my marriage challenges their faith and interferes with their ability to live the lives they feel entitled to live?

What is any of this if not “difference made legal?” If not a constant reminder of my lesser-than status, as King discusses here:

“Any law that uplifts the human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregations distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority.”

That last sentence is so powerful, the idea of giving the segregated a “false sense of inferiority.”

And how true it is.

The simple reality is, for all the advances in recent days, we still live in a nation that imposes a vast number of unjust laws where we are concerned. And a nation in which the religious culture is one that further forces us into segregation and does everything it its power to instill this “false sense of inferiority.” Often, we are unwelcome in churches if we present ourselves in an honest and forthright fashion. We are spoken about in the fashion of Leviticus: Abomination. Or at least politely asked to remain invisible.

Which is to say nothing of the “trickle down” impact that these religious injunctions have on the culture as a whole, and on every aspect of our lives, from family and home to the workplace.

Gay men and women have this in common: we have, until recently, had to hide in plain sight. To segregate ourselves. We have had to live in denial of self to some degree or other—from the closeted to the neutered, comic creatures who turn up as supporting sitcom characters—in order to survive. Even in the bastion of Blue States, the “Capital of the World,” Manhattan, two men walking hand in hand are asking to be hit over the head, spit upon and left for dead. Even today. Even now.

We are segregated, as a group and, especially (given the degree of invisibility of our true natures) as individuals. And until all of us are free—free to marry, free to love, free to live fully-sexual lives—none of us are free.

It is not enough to hide out in the relative safety of Connecticut if those in Oklahoma and Texas and Arizona are denied the rights we enjoy.

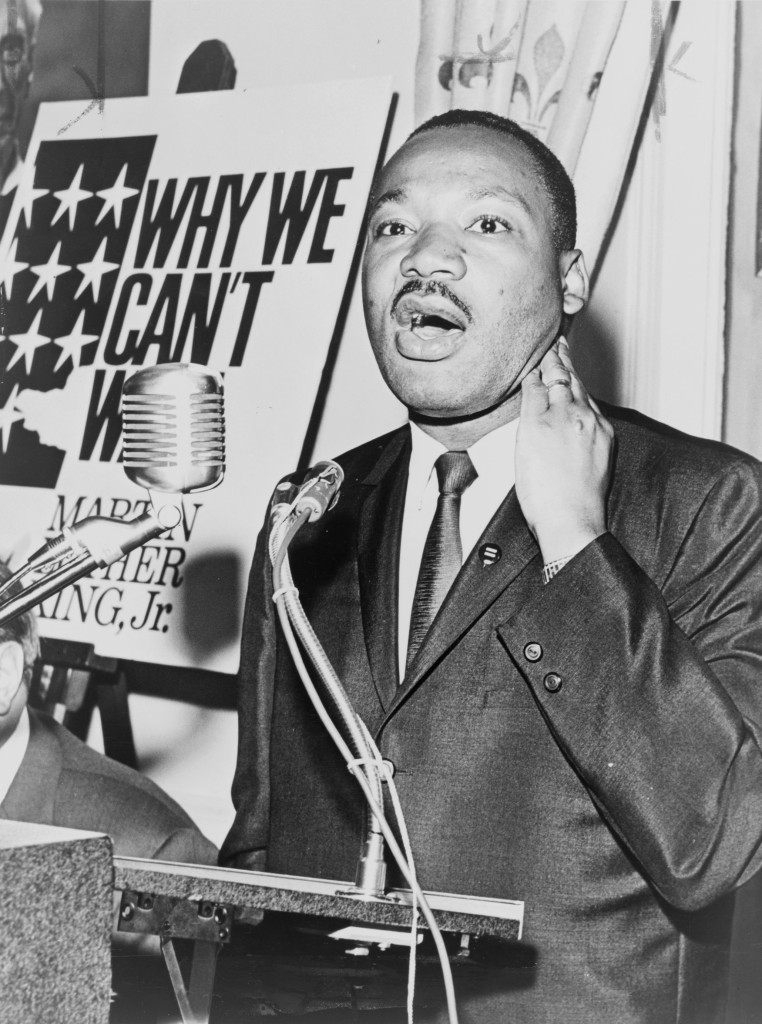

I can’t help but wonder, at such an important moment in history—one in which even the Supreme Court, a court inferior enough to believe that corporations are people and, apparently, that there should be no limit to how much money is allowed to taint the political process—where our Martin Luther King, Jr. is to be found. Why we are still clinging to Harvey Milk, a great man to be sure, but one who has been dead for, what, forty years now, as the leader of record? How can it be that such a talent pool produces so little talent?

I can only speak for myself, but I am weary of the status quo. Indeed, I am made more weary by the fact that the status quo has become such a quagmire that I can’t even be sure of who I am seen to be, under the law, by society as a whole, by the church, etc. (Although you have got to kind of love that new Pope.) To be sure, this is a time of churning waters, of great change, and great strives have been made. But it is vital that we remember that, as King says of his own struggle, the majority never happily hands over equality to the minority—the minority has to take it.

Folks like Larry Kramer who a generation ago shouted to the rest of us, “Come out, come out, wherever you are!” began an awakening. Not only did we as individuals begin to think that perhaps we were actually worthy of being able to be our essential selves AND being fully equal citizens of this nation—and of heaven—but, in doing so, in simply declaring ourselves (“I believe he is speaking to and about me.”), we showed the world that we, the invisible ones, had been by their sides all along. By willingly becoming visible at last, we showed all those around us that were and are their brother and sisters, their mothers and fathers, their co-workers, their friends, their neighbors, the persons in the next pew.

And this is where the change began.

And this is where the heartache began and the source from which it continues.

To get back to Dr. King’s letter, he writes:

“I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice…”

In the same way, I can’t help but think that it is often our heterosexual “friends” and “allies” who hold us back. It is the mother who says, “Can’t we get through one Christmas without having to discuss this?” when her son wants to bring his boyfriend home to meet the family. It is the ally who wants to have the freedom to talk about his or her own relationship while entrapping his gay friend in the role a celibate buffoon. It is the Christian brother or sister who pays lip services to loving support and then lets it stop there, with coffee klatch endearments, always short of risk, and short of action.

I have wondered for a long time now where the Christian moderates and left had gotten themselves. For twenty good years now, we have had to all live under the hammer of the Christian right, a group of loudmouth thugs who curry their power in no small part from their ability to reduce Scripture down into bite-sized bits—with no more value than fortune cookie aphorisms—which they use as the bullets in their righteous guns. Forgetting all context, all actual meaning, they lock and load with, what, six or seven scriptures—the sum total of what the Bible has to say directly on homosexuality—and aim these unerringly. We have been held in check by this handful of words, all taken from context, all ignoring the myriad things that Christ had to tell us about the way in which we should live. We have been tarred and feathered with the word Abomination—a word, to me, more hatefully intended than faggot—to the point that many of us, myself included, have come to own the word, however hatefully it is meant in the mouths of others. We have come to think of ourselves, if not as Lesser, then surely as different, as Other.

Is this the full extent of the change, of our development and growth, both as individuals and as a minority part of American society? Is it sufficient that we have gone from being deplorable things worthy only of derision and disgust to now being simply legally different?

And where in all of this, in the times of travails great (lack of marriage equality, job equality, housing equality, personal safety) and small (no cake) have the majority of the Christians been hiding themselves? Those who uphold the faith, the precepts of Christ, and abhor what the religious right have said and done, where are they? Is this a case of those “white moderates” once more wondering why we can’t just get through another Christmas in peaceful harmony, no matter what the cost?

It is high time that the Christian majority (and, for that matter, the greater circle of gay allies, religious or not) to take an actual stand. I mean, even the Pope is proving capable of thoughtful discourse on this subject.

Or, at the very least, it is time for them to step forward, identify themselves publicly and enter into a conversation.

I truly do appreciate it when a very nice heterosexual says to me in essence, “I support you as a fully equal person (even if I have to close my eyes when I think about what you are getting up to in bed).” But, honestly, it means nothing more to me than “nice shirt” unless it is backed up with a willingness to do more than support me one-on-one in the privacy of the kitchen table. That support needs to be shouted from the pew and reflected in the voting booth. It needs to be taken to the streets. It needs to be stated in print in the local paper and blogged about again and again. Until it is HEARD.

Such support involves risk. All such support always involves risk. Equality is never freely given to the underclass—to the minority group that society has decided is Lesser, Other, or, in this case, Abomination. Or even to those of us asked to remain Invisible and Quiet.

I guess what I am asking for is for all the allies to stand up, throw open your windows and point at random homosexuals on the street and shout, “Let them eat cake!” And then not stop demanding it until all of us get some. How long must we wait?

[box type=”bio”]

VINTON RAFE McCABE is the author of ten books on subjects related to health and healing,

VINTON RAFE McCABE is the author of ten books on subjects related to health and healing, including The Healing Enigma

and Greater Vision

, as well as of the forthcoming novel, Death in Venice, California

. He has worked in both print and electronic journalism, has produced television for PBS and is an award-winning poet and produced playwright. McCabe is a literary critic for The New York Journal of Books.

[/box]