For many, coming out is liberating…

For many, coming out is liberating…

But it’s not always this way. Some people are outed. Some are found out. Some are forced to come out ahead of schedule. Some never come out at all, spending their lives living out the fantasy of what it would mean to be someone else, something else.

When people ask me about my coming out story, I very often start with a little laugh, followed by “It’s complicated.” And that’s because it is. Far more complicated than I would have ever imagined or wished for myself.

I wish I could have simply said, “Mom. Dad. I’m gay,” received hugs and kisses and words of affirmation. I wish I’d been able to actually call myself gay earlier and been okay with it. I wish I’d had different feelings about what it would mean for my life for me to be a gay man. Alas, this was not the case for me.

I knew I was gay when I was nine. Maybe even earlier (thank you hindsight… you’re a loathsome bitch). And I don’t mean simply different. I mean gay. Card-carrying, boy-loving, vagina-loathing, showtunes-singing, hip-swishing gay. But as a Southern Baptist boy growing up in northern Kentucky, there was no way for me to let this cat out of the bag. And the truth is, back then, I did not want it to be true. In my world (and the world of many others from religiously conservative families and communities), gayness was bad. Really bad. Potentially doomed to hell for all of eternity bad.

So I did what any good mom-and-grandmother-loving Christian boy would do:

I faked it. Most of the time. At least I tried.

I had girlfriends from fifth grade through twelfth, some because I genuinely liked them, and some because I so desperately hated the idea of being alone. Some I kissed. Some I groped. One I even made out with (she’s still my favorite). I was never intimate with any of them. It felt too wrong, too dishonest. In conversations I’ve had with some of them over the years, they admitted their suspicions. Some were angry with me for not “trying harder.” Others were saddened by the pressure placed on me to conform rather than be authentic.

The fall of my sophomore year, after spending the summer in Kentucky and discovering this beautiful thing called the internet (and that other thing called porn), after spending day after day in AOL chat rooms talking with people I’d never meet, writing out fantasies that had been begging for years to be uncaged, I came home to find that my own parents bought a computer of their very own. Being as technologically inept as they were, they offered me online time in exchanges for services and education. But I was stupid, did not cover my tracks (because of course my habits didn’t change), and was found out (imagine how bad you think this was, and multiply it by ten or a hundred). I was banned from their computer (for life—I still have not touched a computer of theirs since that day). I still remember the look on both their faces, the disgust in their voices, the distance and detachment in their body language.

Several years passed before I could ever use the actual word gay for myself

I confided in youth group leaders, some of whom responded well and with kindness while others responded with uncertainty, detachment, and even betrayal. I connected with Living Hope, an affiliate of Exodus International. I found a Christian counselor (I will not use the word therapist here) who was willing to help me try and change my sexual orientation. At the same time, I began having my first “encounters,” until finally, one day, I realized that I would always love men and never love women—at least not in the way the world around me told me I should.

I started calling myself gay. I stopped calling myself Christian. And something inside me that day, that moment, died.

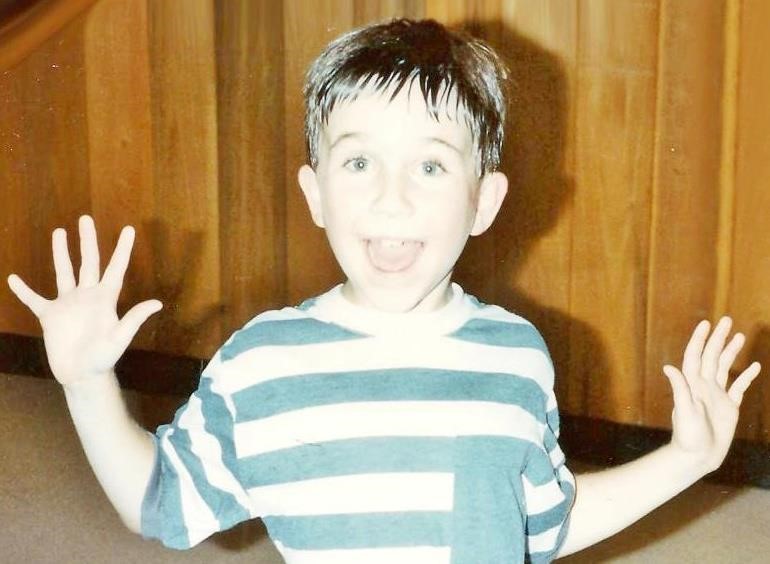

It usually comes as no surprise to people when I tell them I’m gay. My cousin Mattie once told me she knew when I was six, and looking back at a picture from around that time, she’s right.

Seriously. Jazz hands at 7 years old. How could anyone have ever had a doubt?

Seriously. Jazz hands at 7 years old. How could anyone have ever had a doubt?

Here’s the thing: I love my husband, Frank. We’re good together. He’s good for me. And even if those relationships didn’t work out, I’ve loved each of my past significant others. But some days, sometimes, I don’t love being gay. I don’t love coming out to a new person. I don’t like thinking about whether to use the term husband or partner. I don’t always like that there’s a 4 (or 8/9/17) letter acronym used to identify me and people like me. I don’t like that we have to go to court to have not only our legal rights recognized and granted, but also our status as human.

Talking with a friend (and professor) the other day about grief, I realized that part of my own unfinished grief has to do with the remaining desire to be straight. To fall in love with a women. To not cringe (or feel nauseated) at the idea of being intimate with her. I wonder what it would have been like had things turned out differently, but some questions never get answers. Some fantasies never become reality. Some hopes never stand a chance.

I don’t pretend to speak for others on this. I also don’t think I’m the only one to have experienced this. People talk about the grief that parents of queer kids face when they come out. What doesn’t get talked about is the fact that sometimes the queer kids have to grieve the exact same things.

The next time someone comes out to you, think about this. Pay attention to their tone of voice, eye contact, and body language. They might be perfectly fine with who they are. But don’t assume that’s always the case. Sometimes, they’re still grieving…

[box type=”bio”]

MICHAEL OVERMAN is a seminarian at Garrett-Evangelical in Evanston, IL. As a self-admitted “old soul”, Michael is more than comfortable asking the tough questions and not having immediate answers. Michael is passionate about all things interfaith, challenging the religious status quo — and baking whenever possible. A graduate from Trinity Christian College in Palos Heights, IL with a BA in psychology, Michael believes Emma Thompson in Angels in America when she says, “In the new century, I think we will all be insane.”

Find Michael on Twitter @UnfoundBalance or catch up on his blog at www.FindingTheBalance.net.

[/box]