One of the things I love about our ancient texts is their ability to continue to speak to us if we’re in the right frame of mind to listen.

Jonah is one of those weird books in the bible. If you grew up in Sunday School, you learned about the great fish that swallowed Jonah because he refused to follow a divine prompting to go help the people of Nineveh, and how 3 days later it vomited him up, and he finally got on with his assignment. Rabbis and scholars debate the meaning of the book, some thinking it is intentional satire – not meant to be taken literally – to mock Israel’s smugness and self-righteousness, and show in contrast how “pagans” sometimes respond better to God. (The contemporary parallels are obvious.)

This Sunday’s lectionary reading focuses on Jonah after he gets vomited up. And some of the words ring something inside me.

“The word of the LORD came to Jonah a second time, saying, ‘Get up, go to Nineveh, that great city, and proclaim to it the message that I tell you.’ So Jonah set out and went to Nineveh …”

A couple of things jump out to me.

First, “the word of the LORD came to Jonah.” I find myself saying this a lot recently, to friends who are wrestling with God or their consciences over stuff, looking for new insight, new direction. “God speaks.” Whatever we may think about the supernatural, whatever our metaphysics, I believe the Ultimate Source is directly interested in us as individuals, and that Source is always whispering. The question is, will we tune in and listen? Sometimes, like Jonah, it takes a system-shocker to get our attention. That’s never pleasant, but we all know life is complicated. And somehow, even in crazy, confusing times, there is a great deal of comfort in knowing “the word of the Lord” still comes.

Second, it came to Jonah “a second time.” This is so cool. Cuz often we don’t listen the first time. Even if we’ve put in our meditation time, quieting the riot in our brains long enough to get some peace and clear our mental filters so we can tune in to that Cosmic Voice, we will just as often forget what we hear. We’ll put it down. Or maybe just reject it outright (like Jonah). It is reassuring to me to know that that Voice is patient, it will persist. Even if we miss it, it is happy to whisper to us again.

Third. “Get up and go … and proclaim the message I will tell you.” This is the beautiful ambiguity in our divine promptings. I think the author of Jonah is directly borrowing language and imagery from one of Israel’s national identity stories: the calling of Abraham. In that story, God tells Abraham “leave your land … and go to a place I will show you.” There are the same two potent elements: the command to “get up and move!” and the surprising lack of definition about “where or what.” In Jonah’s case, we’re not told — he’s not told — exactly what he’s supposed to say when he gets to Nineveh. His first obligation is just to get his butt up and move. The specifics will follow. Clarity follows our initial movement. You won’t get the full instructions on the first phone call. You don’t get the complete road map with the invitation. Like that famous proverb from the Tao Te Ching says, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” An alternate translation of the proverb reads ” … begins from under the feet.” That is, it’s right there in front of you, under foot. You just gotta take that first step; you gotta get up off your butt and move.

And so, like Abraham, “Jonah set out and went…”

So many of us sense something is ahead. I guess that’s appropriate. We’re still so close to New Years when many of us feel the urge for fresh beginnings, new starts or restarts. But regardless of the calendar, regardless of our age or current situation in life (“you’re not done yet!”), if you’re feeling that weird, undefined, ambiguous pull, and suspect there are divine fingerprints on it, sit up and listen. Even for the second time. Cuz fresh adventure awaits. And sometimes it’s just needing you to take that first step.

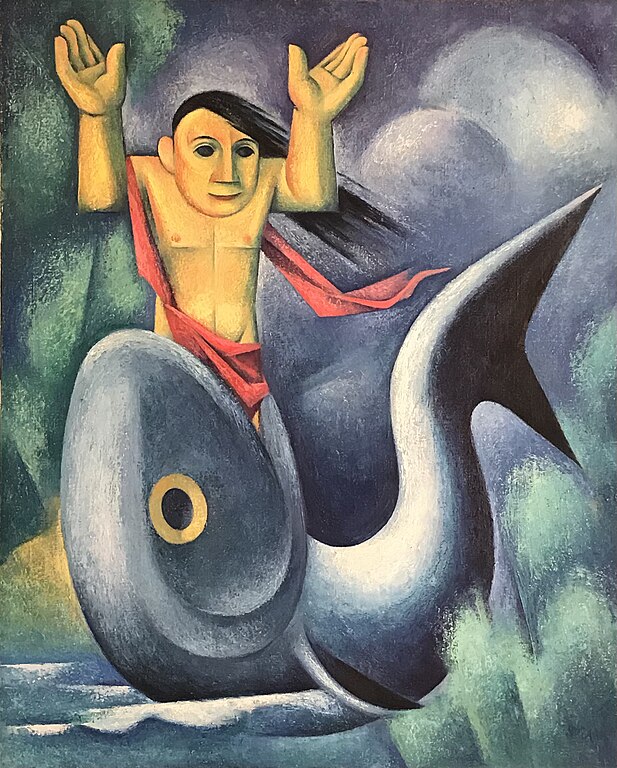

image: Josep Maria de Martín i Gassó, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons